The Legend and the Man

from:

"The Legend and the Man," in The World of Rembrandt: 1606-1669 (Time-Life Library of Art), Walter Wallace, New York, 1968, pp. 17-25

In life Rembrandt suffered far more misfortune than falls to the lot of an ordinary man, and he bore it with the utmost nobility. Three centuries after his death the misfortune, if a man long deceased can be said to endure such a thing, continues. To be sure, it is no longer the fashion for critics to attack him both as artist and human being. Today the injury is done with a fond smile by writers of romantic biographies and films who mean to honor him. Their revised standard version of Rembrandt's life runs approximately as follows:

"The child of poor, ignorant Dutch peasants, Rembrandt was born with near-miraculous skill in art. As an uneducated young man, he established himself in Amsterdam, married a beautiful, wealthy, sympathetic girl named Saskia, and enjoyed a brief period of prosperity and fame. However, because men of genius are always misunderstood by the public, fate snatched him by the throat. The important burghers of the city, who may not have known much about art but knew what they liked, gave him an enormous commission - the Night Watch - in which the burghers were to be painted in traditional postures and lights. Rembrandt responded with a masterpiece, a fact unfortunately apparent only to him and his wife. Everyone else, from the burghers to the herring-peddlers, thought the painting was dreadful. Rembrandt's patrons hooted in rage and derision, demanding changes that the artist, secure in the knowledge that posterity would vindicate him, stubbornly refused to make.

"At this point, because it is not customary for a genius to suffer a single setback but to be overwhelmed by multiple catastrophes, Rembrandt's wife died, the Night Watch was ripped from the wall and placed in some indecorous location, his friends deserted him .and he was hounded into bankruptcy. In his final years no one would commission a painting from him; he was reduced to making self-portraits, which he did whenever he could cadge the necessary materials from his art-supply dealer. His only comforters were his san Titus and his mistress Hendrickje, both of whom died in heartrending circumstances. Prematurely aged at 63, he passed away in such obscurity that the burghers, observing his pathetic funeral, inquired, 'Who was he?' However, even at that dark hour the mills of the gods were slowly grinding, and in our own time the verdict in favor of Rembrandt's greatness has been amply reaffirmed by the trustees of New York's Metropolitan Museum, who not long ago paid 52.3 million for his Aristotle Contemplating the Bust of Homer and were very lucky to get it at the price. Indeed, as the Metropolitan's director Thomas Hoving recently remarked, 'Look at that chain [on Aristotle's shoulder]. That alone is worth two million three!' "

The foregoing summary is an interesting and tidy one, and presents the view of Rembrandt generally seen by the world. In most respects, however, it is dead wrong. Rembrandt was not a peasant nor was he uneducated. The Night Watch did not bring about his downfall; indeed, he never had a "downfall" in the dramatic sense. And when he died, there remained more than a few people who held him in the highest regard. Nonetheless, myths die hard, and that of Rembrandt is durable. In the United States the myth is particularly widespread, in part because of a 1936 film in which Charles Laughton portrayed the artist. Despite its age, Laughton's Rembrandt remains a valuable commercial property, is frequently shown on television, and has been seen and presumably accepted at face value by an enormous number of people, upwards of 100 million. However, through no fault of Laughton's, who in private life was a serious connoisseur of art, the script with which he was obliged to work was not a masterpiece of accuracy. Whenever the film is shown, another half-million viewers are exposed to the myth, but whenever a scholar ferrets out a new scrap of truth about Rembrandt and publishes it in an art journal, only a relative handful of fellow-scholars are aware of it. There is, of course, nothing novel in this situation-Michelangelo, Leonardo, van Gogh, Toulouse-Lautrec and others have been similarly treated-but Rembrandt has endured more than the rules of the game should allow.

In Rembrandt's case myth-making comes easily as an alternative to fact-finding. Romantics and scholars alike are handicapped by a scarcity of contemporary information, not only about Rembrandt but about most of the artists who participated in the great sunburst of painting in the Netherlands of the 17th Century. Rembrandt left no journal or notebook, and only seven of his letters have been located-all addressed to the same man, concerning a specific project and revealing little of his thought or personality. Yet even this thin sheaf is comparatively a rich hoard. From the hands of other major artists of Rembrandt's time - Frans Hals, Jan Steen and Jacob van Ruisdael - not a solitary note has been found. Possibly Dutch artists rarely wrote letters, but it seems more likely that their correspondence was not thought worth keeping.

Because Rembrandt himself is almost mute - except in the majestic eloquence of his art - it is necessary to turn for information to other 17th Century sources. The Dutch archives, however, contain only one document of real interest: the inventory of Rembrandt's possessions at the time he declared himself insolvent. Otherwise there are only the bare bones of history - records of baptisms, marriage and deaths. The accounts of contemporary biographers are few and in several instances misleading. The first treatment of Rembrandt, which appeared in 1641 as part of a history of his birthplace, the town of Leiden, was written by a onetime burgomaster, Jan Orlers. Nothing in Orlers' work has been found to be inaccurate, but it covers less than half of Rembrandt's artistic career - his early years - and is only a few hundred words in length. In 1675, six years after Rembrandt's death, Joachim von Sandrart, a German artist who had known him, produced a memoir of about 800 words. These two meager accounts, plus some observations in the autobiography of the Dutch scholar-statesman Constantin Huygens, constitute almost the entire body of material written by men who had first-hand knowledge of Rembrandt.

In 1686 an Italian churchman and art historian, Filippo Baldinucci, who obtained his information from one of Rembrandt' pupils, published a brief commentary about him as part of a volume dealing with many graphic artists. It was not until 1718, nearly a half-century after Rembrandt's death, that the first full-dress biography appeared-and even that is very slim by modern standards. Written by Amold Houbraken, whose De Groote Schouburgh der Nederlantsche Kunstschilders (Great Theater of Netherlandish Artists) remains the best source-book on Dutch artists of the period, it contains valuable comments on Rembrandt's work as it was then viewed. In areas outside art, however, it has proved as vulnerable as earlier accounts. Sandrart had implanted the legend that Rembrandt was an ignoramus who "could but poorly read Netherlandish and hence profit but little from books." Baldinucci left the misinformation that Rembrandt worked for the court of Sweden. When it was Houbraken's turn to set down the facts, he mislocated the artist's birthplace, added five years to his life and noted that he was an only son (Rembrandt had four brothers).

It may appear picayune to dwell on these errors, but they make it difficult not to raise an eyebrow at some of the tales Houbraken supplies when he sets out to describe Rembrandt as a man. Houbraken says, for example, that Rembrandt was a miserly soul whose avarice was such that "his pupils, who noticed this, often for fun would paint on the floor or elsewhere, where he was bound to pass, pennies, two-penny pieces and shillings ..after which he frequently stretched out his hand in vain, without letting anything be noticed as he was embarrassed through his mistake." The biographer also reports that Rembrandt, who willfully broke all the "rules," once "painted a picture in which the colors were so heavily loaded that you could lift it from the floor by the nose." Other stories, however, are not so easy to reject. There is some evidence that Rembrandt was at times irascible and whimsical. According to Houbraken, "One day he was working on a great portrait group in which man and wife and children were to be seen. When he had half completed it, his [Rembrandt's] monkey happened to die. As he had no other canvas available at the moment, he portrayed the dead ape in the aforesaid picture. Naturally the people concerned would not tolerate the disgusting dead ape alongside of them in the picture. But no: he so adored the model offered by the dead ape that he would rather keep the unfinished picture than obliterate the ape in order to please the people portrayed by him." Possibly the tale is true. Rembrandt was a man of highly independent mind, delighted in drawing and painting animals, and may have thought the dead monkey more interesting than the particular family he was dealing with.

The relative lack of accurate contemporary accounts of Rembrandt is not the result of carelessness or loss through the centuries, nor is it because he was not widely known and admired during his lifetime; he was. The difficulty stems in large part from the temperament of the Dutch people, who have never been at ease in the world of reflective or descriptive prose. They take the view that a painting is to be looked at, beer is to be drunk and life is to be lived - without the aid of a tedious libretto. With one or two notable exceptions, the Dutch nave not produced poets, playwrights, novelists, letter-writers or critics of the first rank. They prefer to act and wordlessly to contemplate, not to involve themselves in comment or analysis, and thus during the golden century of their art they made only sparse notes about their greatest painters.

This reticence in prose had its counterpart in art. During Rembrandt's lifetime the Dutch people, numbering fewer than three million, accomplished prodigies. They threw off the yoke of Spain and established an independent nation. On the sea they challenged England and for a time forced that great maritime power into second place. The Channel and the North Sea, the green, rich Indies of the East and West heard the thunder of their cannon and saw the triumph of their flag. But Dutch artists rarely glorified such things; instead they perfected the still life.

Fortunately, the advanced research techniques of modern scholars, spurred by the commemoration in 1969 of the 300th anniversary of Rembrandt's death, have made it possible to extract a good deal of new information from the silent past and to correct errors made in the intervening centuries. Sandrart's view of Rembrandt as a semi-literate has been demolished, and so too--at least among students of art history--has been the notion that the Night Watch marked a sudden, dramatic downturn in Rembrandt's fortunes. It is now known that the artist never went to Sweden, nor did he, as other old legends insist, reside for a time in England or travel in Italy. Thus, even if frequently through the correction of mistakes, the state of knowledge about him has been considerably increased. In relation to the remarkable breadth and depth of Rembrandt's art it is fascinating to find, at long last, that he may never have left his homeland; indeed, that he probably. passed his entire lire within a radius of only a few score miles. All his voyaging was done on the inward sea of his own spirit.

In any case the real measure of Rembrandt is to be found in his works, and even a hasty glance at them reveals much that is not included in his myth. Although he is commonly associated with only a half-dozen paintings. The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Tulp, the. Night Watch, The Syndics of the Drapers' Guild, the Aristotle and Homer, and two or three self- portraits - he was, in fact, one of the most productive artists the world has known. As many as 2,300 of his works survive and have thus far been identified-some 600 paintings, 1,400 drawings and 300 etchings.

It is possible that still others will come to light in our rime. Once recent identification of one of his paintings was made only in 1780. Although it is not a great work of art, it has considerable importance because it is Rembrandt's earliest known dated painting. Executed on a wooden panel, it depicts his version of the martyrdom by stoning of St. Stephen. Long the property of the museum of Lyons in France, it was attributed vaguely to "the school of Rembrandt" and relegated to a storeroom until two Dutch scholars, suspecting its true authorship, suggested that a comer of it be cleaned. A few swipes of the swab revealed the undoubted monogram of the master and the date, 1625, when he was only 18 or 19.

Although there is a possibility that some Rembrandt drawings, or even a cache of them, will turn up one day in an old chest or bureau drawer, the likelihood of a major discovery is not great. Collectors and connoisseurs have apparently exhausted the field. However, single drawings are still occasionally found. The task of firmly attributing a drawing to Rembrandt is by no means easy; he was a prodigiously active draftsman who rarely signed his small sketches and used whatever paper he happened to find handy, including printed pages, the backs of bills and even of funeral announcements. Most of his drawings can be identified only on stylistic grounds, and in this area scholars are not in unanimous agreement.

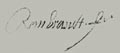

Among the 2,300 works there are at least 90 self-portraits - 60 of them paintings and the rest etchings and drawings. In addition, Rembrandt's face appears in at least five other works as that of a spectator or participant in the action. No other great artist is known to have represented himself so frequently, which suggests a well-developed vanity on his part - until the portraits are studied. Although there were occasions in his young manhood when he may have wished to appear handsomer than he was, and although he sometimes used his own face merely as a model, contorting it into expressions of anger, joy or shock, he took, in general, a very penetrating, even merciless view of himself. Rembrandt's overriding artistic concern was with the human spirit or, in a phrase that appears in one of his letters, with expressing "the greatest inward emotion." In his quest for an understanding of mankind he found it necessary to begin with self-searching; in the visual arts no one has more closely followed the ancient Greek dictum, "Know thyself," with all the courage that such a seemingly simple injunction demands. A moving spiritual autobiography can be extracted from his self-portraits, but it is best to turn first to the physical events of his early life.

Self Portrait as a Young Man

c. 1628

22.5 x 18.6 cm.

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn was born in Leiden, about 25 miles south of Amsterdam, on the 15th of July, 1606. His father, Harmen, was a miller whose surname, van Rijn, indicates that the family had lived for some generations beside or near the Rhine River. His mother, Comelia (or Neeltgen) WilIemsdochter van Zuytbrouck, was a baker's daughter. Traditionally their large family - Rembrandt was the eighth of nine children - has been described as poor and struggling. The artist's vitality and his almost ferocious energy, some critics suggest, derived from his "peasant" background and his desire to rise above it. However, there is no evidence that the van Rijns were impoverished potato-eaters.

When Rembrandt' mother died in 1640 she left an estate valued at some 10,000 florins. The precise value of that currency is very difficult to calculate now, but it is known that the wage of a 17th Century Dutch craftsman - a weaver, for example-was only three or four florins for a 12-hour day. Thus it appears that the family was fairly well-off. In some of his early self-portraits Rembrandt chose to represent himself as a beggar and as a young rebel who appeared to have a grudge against the world; his face was wide, with small eyes, a broad nose and powerful jaw. But these are not necessarily the features of a country clod, and if Rembrandt had some quarrel with the world it may have been rooted in his anger at the inhumanity of man rather than in his family circumstances.

Rembrandt's birth coincided closely with that of the Dutch nation. For generations the 17 provinces of the Low Countries (the Netherlands, Belgium and Luxembourg) had been under the rule of Catholic Spain. However in 1609, when Rembrandt was three, the seven northern provinces under the leadership of the noble House of Orange, finally achieved the freedom for which they had been struggling for 40 years. Spain did not formally recognize their independence, but in fact the Spanish were seldom again a serious menace to Dutch liberty. The United Provinces, as the nation was then called, included Holland, Zeeland, Utrecht, Guederland, Overijssel, Frieslànd and Groningen. Of these, Holland was the wealthiest and most populous and for that reason its name was frequently used by foreigners to refer to the whole country, to the annoyance of the citizens of the other six provinces.

The new nation was democratic in its institutions and vigilant in safeguarding them. The House of Orange, however successful it had been in rallying and leading the people, was unable to form a strong central movement. The various provinces sent representatives to the modest court at The Hague, but each province regarded itself as autonomous in all matters save defense and foreign policy.

In this loose federation, the two traditional sources of patronage for artists were no longer available. During the first decades of their freedom the egalitarian Dutch cared little for titles and the courtly life, and although the House of Orange did commission works of art (including at least seven paintings by Rembrandt), aristocratic patronage was negligible. The other source of patronage, the Catholic Church, was also shut off. While Catholics still formed a sizable segment of the population when the United Provinces carne into being, gradually they were sumerged in the rising tide of Protestantism, particularly Calvinism. More and more, the Catholic faithful were compelled to worship in private - their churches were stripped of their altars and often were taken over for use by Protestants. In these circumstances, the Church could no longer supply the rich commissions that had nourished artists since the beginning of the Renaissance.

Thus, for the first time in history, painters assumed the independent but precarious position in society that-they still occupy. Fortunately for 17th Century Dutch artists, of whom there were literally thousands, the ordinary citizens of the country replaced the Church and the aristocracy as purchasers of paintings. (Sculpture never became a major art form among the Dutch. There is no facile explanation for this; perhaps it was because monumental sculpture seemed out of place in the comfortable decor of a middle-class home, or perhaps it was because the solid burgher, who might pay a fair sum for a canvas, found his sense of propriety offended by the notion of something so grandiose, and reminiscent of "popish" church art, a statue.)

Self Portrait

c. 1652

203 x 134 mm.

Museum het Rembrandthuis

Amsterdam

The extent to which the average Dutchman participated in the art market is almost beyond belief. If a rough parallel may be drawn, the situation will be comparable when every second family in the United States possesses an original painting. As to why the Dutch were so fascinated by art, there is again no ready explanation. This was simply the particular form of creativity that appealed to them and for which they had enormous talent. To be sure, the typical citizen was inclined to regard painting merely as wall decoration, and his taste tended strongly to an almost photographic naturalism in portraits and scenes of everyday life, but he bought canvases in remarkable quantity. The English traveler Peter Mundy, who visited Amsterdam in 1640, noted with some astonishment that as for the Art of Painting and the affection off the people to Pictures, I thincke none other goe beeyond them there having been in this Country Many excellent Men in that Facullty, some att present, as Rimbrant, etts., All in general striving to adorne their houses, especially the outer or street roome, with costly peeces, Butchers and bakers not much inferior in their shoppes, which are Fairely sett Forth, rea many tymes blacksmithes, Coblers, etts., will have some picture or other by their Forge and in their stalle. ..."

In such a climate it was natural for artists to be extremely productive. If it can be believed, it is recorded that Michiel van Miereveld, an able Delft painter, produced more than 10,000 portraits in his career. Miereveld lived to be 74, and if he began painting at 14 and continued for 60 years, his output averaged better than three portraits a week. It is also record ed that Cornelis Ketel, another good artist, who apparently became bored with the endless turning out of portraits, used to amuse himself and his clients by painting with his toes.

As may be suggested by Miereveld's and Ketel's activities, the Dutch artist of the 17th Century was frank to acknowledge himself as a craftsman, a producer of goods. Although such masters of the High Renaissance as Leonardo and Michelangelo had made it very plain, in the Italy of the preceding century, that art was no mechanical exercise but the loftiest of callings, Dutch painters had little of that sentiment. In general they accepted their fairly humble status (Rembrandt took exception to this) and asked no special deference. As a rule they did not feel called upon, as had the Italians, to write augmentative treatises to explain themselves and their theories-and therein lies still another reason for the sparseness of knowledge about them.

Despite the vigor of the art market, exceedingly few Dutch painters prospered and died rich. An oversupply of paintings depressed prices, with the result that a good canvas sometimes sold for as little as 10 or 15 florins. Rembrandt, at the height of his popularity, received the resoundingly handsome sum of 1,600 florins for the Night Watch, and later became bankrupt not through lack of good commissions but through mismanagement of his affairs. But other fine artists were forced to become tavernkeepers or ferrymen in order to make ends meet. It is said that Hercules Seghers, whose romantic scenes influenced Rembrandt's landscapes, withdrew tram the struggle and died an alcoholic. Frans Hals and Meindert Hobbema had grim financial problems. Jan Vermeer at the time of his death owed a baker's bill of 617 florins, for which the baker (no doubt grudgingly) was obliged to accept two paintings, their identity since lost that might have made his descendants incalculably rich.

Rembrandt's decision to become an artist, or perhaps more accurately his parents' decision to establish him in such a chancy career, was not taken early. As a boy he must have impressed his parents as the most promising of their children--of their other sons who survived to manhood, one be- carne first a cobbler and then a miller, and another a baker - and accordingly they sent Rembrandt to the Latin School in Leiden to prepare him for a learned profession. In the United Provinces it was not unthinkable that a miller's son could aspire to any position, however high, and his parents evidently knew the value of an education. Among Rembrandt's drawings there is one which shows a small family group, probably his own, seated around a book on a candlelit table. His mother, whom he often portrayed with a Bible on her knees and who several times served as a model in his Biblical paintings, was a devout reader of Scripture; doubtless he first absorbed from her the sense of God, man and nature that was to make him the most profoundly Christian of all Protestant artists.

Self Portrait as Zeuxis

c. 1662

82.5 x 65 cm.

Wallraf-Richartz-Museum, Collogne

The Latin School, which Rembrandt attended from his seventh to his 14th year, placed heavy emphasis on religious studies. Its curriculum, apparently unknown to early writers who commented on Rembrandt's ignorance, also included the reading of Cicero, Terence, Virgil, Ovid, Horace, Caesar, Sallust, Livy and Aesop. The students conversed in Latin, and Rembrandt became accustomed to the Latin form of his own Dame, Rembrantus Harmensis Leydensis (Rembrandt the san of Harmen of Leiden). It was for this reason that he signed his early works with the monogram, RHL. Rembrandt not only passed the course, but later recalled it in detail; his historical and mythological paintings reflect meticulous attention to the texts on which they were based.

It was the purpose of the Latin School to prepare young men for admission to the University of Leiden, which in Rembrandt's time was the equal of any in Europe. The French philosopher Descartes, who wrote his Discourse on Method while living in the United Provinces, passed some rime there, as did other scholars of his caliber. In all likelihood, Rembrandt never had much contact with such men, but he early developed an admiration for the "old philosopher" in general, a type that appears frequently in his paintings. Nor did Rembrandt pursue;le his formal education much beyond the Latin School; he went so far as to be matriculated in the University, but withdrew apparently after only a month or two. It was at this point, sometime in 1620, that he turned to art.

The name of Rembrandt's first teacher, mentioned only as "a painter" in old accounts, is unknown. His second under whom he served a three-year apprenticeship, was an obscure and none-too-talented Leiden painter named Jacob van Swanenburgh, who specialized in architectural scenes and views of hell. Van Swanenburgh, like many other Dutch artists of the rime, had studied in Italy but apparently had not profited much from the experience. He taught Rembrandt the fundamentals of drawing, etching and painting but does not seem to have made a deep impression on his pupil. In later years Rembrandt turned his hand to almost every subject that may occur to an artist--except architecture and hell. (Architecture appears in many of Rembrandt' backgrounds, to be sure, but unlike van Swanenburgh he never treated it per se).

From Lastman Rembrandt derived other elements of his early style-the use of bright, glossy colors and lively, sometimes theatrical gestures in paintings of fairly small scale. It was probably Lastman, too, who inspired Rembrandt to become a history painter at a time when history painting was not notably fashionable among the Dutch. Theorists accepted the idea, as they had since the Renaissance, that there was a hierarchical order in the genres of painting. The noblest subject for the artist was the famous past, particularly the Biblical past, while portraits, scenes of everyday life, landscapes and still lifes were of secondary importance. However, the ordinary art buyer in the United Provinces paid little heed to art theory; he preferred subjects from daily life that were familiar to him, and so gave his trade to painters in the "minor" specialties. Nonetheless Rembrandt not only chose to take up history painting but dedicated himself to it with a fervor that lasted all his life. Although he eventually worked in almost all the specialties, he did not paint a commissioned portrait, so far as is known, until he had been established in his career for at least six years and did not "venture seriously into landscape until he was in his late thirties. His preoccupation was always with history and above all with the Scriptures. '.

At 18 or 19 Rembrandt left Lastman, returned to Leiden and set himself up as an independent master. His recently discovered Stoning of St. Stephen, a product of that period, reveals flashes of his genius, but it also reveals what a steep road he had to travel before he could fully express it.